We spoke with Sean Hinton, appointed Chairman of the Board of Directors of Oyu Tolgoi last October. With extensive experience living and working in Mongolia, he has built a distinguished career in international business and impact investment. A British-Australian citizen, he also served as Mongolia’s Honorary Consul in Australia.

You’ve been in the role of Chairman for almost three months now. Also, you have been worked closely with the country on numerous occasions since you have first arrived in Mongolia in 1988. What drew you to Mongolia and inspired your continued involvement?

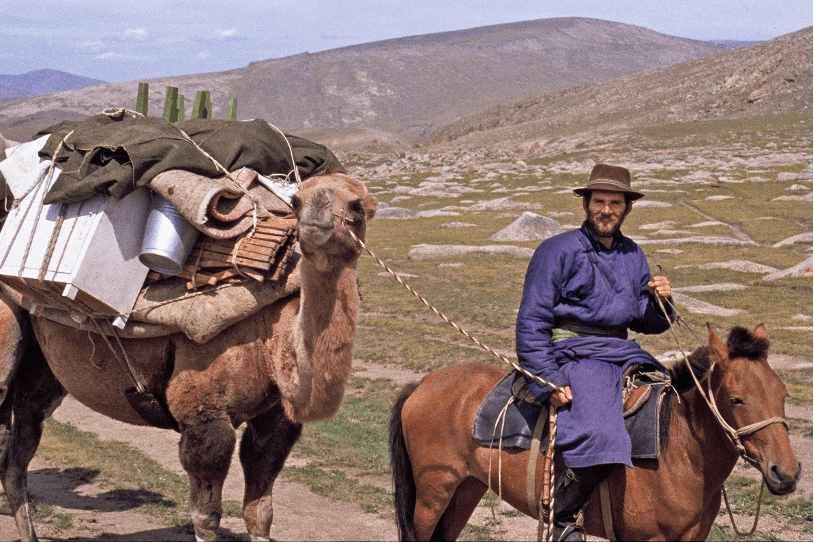

I came to Mongolia first out of a sense of sheer adventure and curiosity. I was 22 years old and was fascinated by a country that had been so isolated from the rest of the world for so long. I wondered what life was like, and in particular whether ideas that I had grown up with and took for granted: ideas about the planet as one whole, and the people of the world as equal and the same, whether I would find people in Mongolia held these ideas too despite its isolation. A year or so after I arrived, Mongolia, and the Soviet world, when through huge political change. I had this extraordinary sense of having, by sheer luck, been a witness to a moment of historical transformation. For younger generations, it’s probably hard to imagine what it was like when everything you thought you understood about how the world was structured suddenly shifted. The East-West divide, the Iron Curtain—that was all we knew in our generation.

I remember when I first came here, even Mongolians needed permission to travel within their own country. For instance, when we boarded a plane to Choibalsan, the police came to check not only the foreigners’ permissions but also the Mongolians’. Then, seemingly overnight, that restriction disappeared, and the whole world opened up.

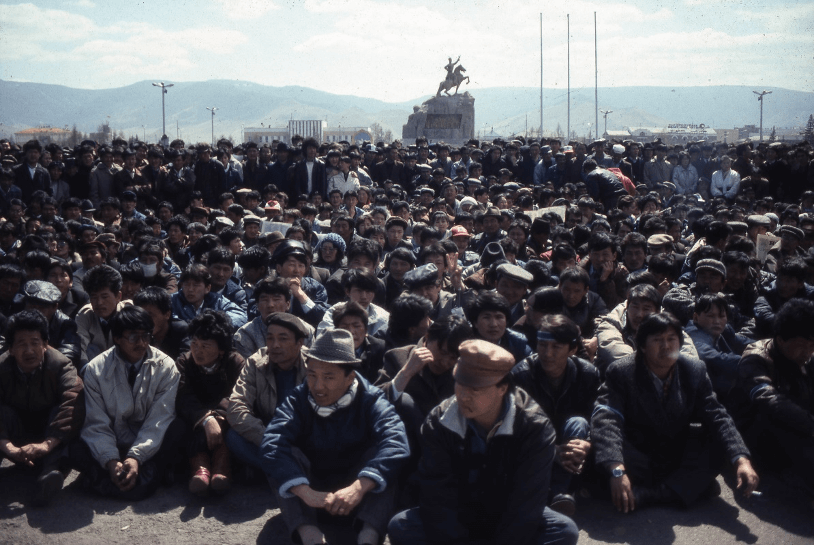

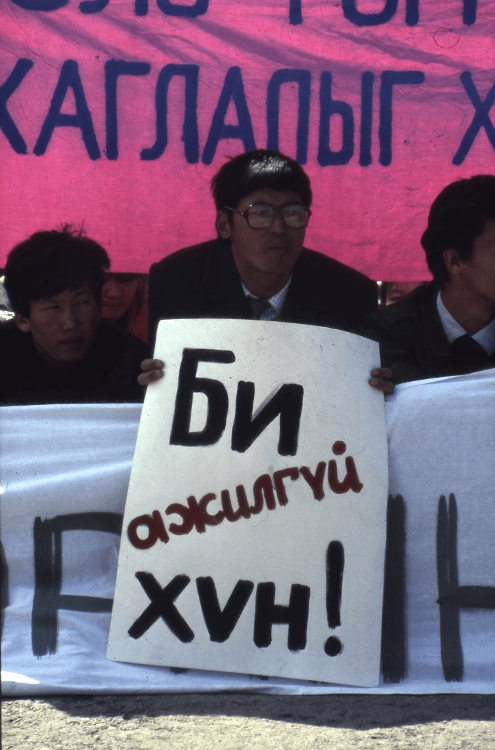

I saw the process of privatization with my own eyes when I was living in Bulgan soum, Khovd aimag. All the livestock that had belonged to the ‘negdel’ was distributed to individuals. And you know, when the students and citizens gathered in the central square, demanding change, I was there. I even have photographs. So, every year, I thought to myself, “I’ll stay one more year and see what happens”, and that’s how I ended up staying here till 1995.

It’s wonderful to be back. I have so many happy memories associated with Mongolia. My wife and I have been married for 32 years, and we spent our first two years as a married couple in Mongolia. Our first apartment was here, and so was our first office.

This is far from your first interaction with OT—you worked as a consultant for OT back in the day.

Yes, at the time, my role was focused on everything outside the mine gate—examining the impact of the project on the local community and the national economy and maximizing its benefits.It was clear early on that OT was far more than just a copper mine. It represented an opportunity for Mongolia to develop and present itself to the world. It happened at just the right moment in the commodity cycle and the global economic cycle; everything seemed to align. That’s why the signing of the Investment Agreement had such a significant signaling effect. Also, Mongolians didn’t just sit back, and hope investors would come—they took action. Mongolia organized investment conferences in Hong Kong and other parts of the world, actively promoting the country and making the most of the opportunity.

We often talk about Oyu Tolgoi as being a big mine, but that’s not what makes it extraordinary. Its importance lies in its complexity. It’s the mining equivalent of going to the Moon.

What will be your main focus as Chairman?

The first area of focus is how the board functions. It’s important to develop a better understanding—both within Mongolia and among ourselves—of the role of the board and, just as importantly, what the board’s role is not. Our job is not to act as another layer of management. I see the role of the chairman as being like the coach of a team, not the referee—bringing the players together, finding common ground and seeing the bigger picture. A key focus for me is on the people-side of the business: how we develop our workforce, build skills beyond our workforce, and contribute to mining and non-mining skill development and leadership.

You know, we often talk about Oyu Tolgoi as being a big mine, but that’s not what makes it extraordinary. Its importance lies in its complexity. It’s the mining equivalent of going to the Moon. They used to say that when rockets were heading to the moon, they were off course 90 percent of the time—not drastically off course, but slightly. While the theoretical trajectory was perfect, reality required constant course corrections. The key isn’t about always being on the perfect path; it’s about having the ability to recognize when you’re off course and make adjustments. This principle is also what I’m trying to instill within the board—flexibility and adaptability to keep us on track. But it should be a source of huge pride for Mongolia, that such a complex and technologically cutting edge mine has been built here, by Mongolians and international partners.

How did the process of you becoming chairman unfold? How did your candidacy come about?

Rio Tinto, as a shareholder, did a formal search process. They hired a headhunter and looked at a whole range of candidates. I believe they were looking for someone who had a deep understanding and appreciation of Mongolia’s unique context—someone with insight into its cultural, legal, and historical frameworks. I was a candidate who they knew already as I had been involved in working with OT from the early days of the project, around 15 years ago, advising on the social and economic impact. So, when they approached me for the position I accepted immediately. It’s an incredible honor and privilege—and a tremendous responsibility. This is likely the most important thing I will ever be a part of accomplishing. The decisions we make at Oyu Tolgoi have a tangible impact on people’s lives—hundreds of thousands of lives.

As you’ve said, your role is to look at the big picture. What is your long-term vision for the company?

The company has a well-defined strategy built around four key pillars. It emphasizes partnership and people —between the company and the government, and between the company and the Mongolian people. It also accentuates the profit. It’s important to recognize that for this project to succeed, it must be profitable for all its stakeholders. Investors are watching to see if this becomes a truly successful project. The sustainable production of our underground mine, which we’ve heavily invested in alongside our partners, is the key to unlocking that profitability. Last but not least is planet. In order to transition as much as 30 percent of the energy we use—currently sourced from a mix of energy types—to completely renewable energy, we’re working closely with the government and the private sector to develop renewable energy plants capable of generating 180 megawatts of power. This is highly scalable, especially in the Gobi, where wind energy has tremendous potential. And we’re conducting trials with battery-operated haul trucks—the first in the world. Rio Tinto hasn’t tried them anywhere else, so this is an incredible opportunity for us.

If you’re building something meant to last for a hundred years, you don’t just work with the best engineers and architects—you also need the best financiers. These financiers not only provide stability but are also capable of adapting to changing circumstances over the long term.

No other board attracts as much attention as Oyu Tolgoi’s. Many people perceive Oyu Tolgoi board members as individuals who earn substantial salaries without contributing much.

Board members are not part of management, so they’re not directly making operational decisions themselves. Instead, they need to develop a deep understanding of complex issues to make informed strategic decisions. It’s a challenging and, frankly, scary responsibility, especially when, like you said, everyone is watching.

Another layer of complexity comes from the fact that our board members are appointed by shareholders. Board members must take the time to fully understand an issue, communicate it clearly to their shareholders.

But I am incredibly proud to serve alongside such a group of highly accomplished and dedicated board members who work incredibly hard, before during and after each and every meeting, and who are really doing their utmost to help OT make the best possible decisions and realise its full potential.

How often do you hold a board meeting?

We meet as a board four times a year. Additionally, we have extra meetings to focus on a major strategic theme or work on something in-depth with the board. The board is consistently faced with a pipeline of new projects, developments, and expansions. This applies to the concentrator, material handling, open-pit development, the underground mine, and tailings facilities.

Why does financing fluctuate so much in mining?

Collectively, we refer to it as Oyu Tolgoi, but in reality, it’s hundreds of big and small Oyu Tolgois that need to be developed and managed. So, we are constantly evaluating and making decisions about capital investments at every board meeting.

We develop the budget annually, but it’s always done in a context of uncertainty. For example, we can make educated guesses about the copper price, but we don’t know for sure—it could go up or down. Similarly, while we know a lot about the ore body, we can’t predict every detail.

To ensure the business is well-prepared, we sometimes have to consider additional financing—like an insurance policy—to address unforeseen circumstances. Our CEO often reminds us that there’s no pause button on a block-cave mine. Once it starts, nature continues its work, and we must keep up with the geology.

Accessing finance for a project like Oyu Tolgoi is highly technical, and the choice of who supplies that finance is really important. If you’re building something meant to last for a hundred years, you don’t just work with the best engineers and architects—you also need the best financiers. These financiers not only provide stability but are also capable of adapting to changing circumstances over the long term. For example, the IFC and EBRD are both deeply concerned about OT’s impact on the environment and local culture, and their involvement ensures these factors are addressed responsibly and this adds value to our own concerns on these issues.

There was a significant reset in the relationship between the shareholders recently, and that created an opportunity for Oyu Tolgoi to really push ahead and get going, which is fantastic. Bringing together the right type of financing isn’t just about cost—it’s about creating a coalition of partners who are fully invested in Mongolia’s future.

100 percent of the people that come to Mongolia do so to see the horses, the steppe, the Gobi, and the landscapes. But 100 percent of them leave talking about the people. Nature may draw them in, but it’s the people who leave the deepest impression.

Thank you for providing such a thorough insight into Oyu Tolgoi’s Board of Directors. My final question is: What has left the deepest impression on you during your years in Mongolia?

The most remarkable thing about Mongolia has always been its people. My first business in Mongolia was a travel company, Nomads Tours, and when I was running that 30 years ago, I learned that 100 percent of the people that come to Mongolia do so to see the horses, the steppe, the Gobi, and the landscapes. But 100 percent of them leave talking about the people. Nature may draw them in, but it’s the people who leave the deepest impression.

Mongolia is a country where people dream big—they believe in the potential for their country to achieve greatness and for their lives to improve. And they have unparalleled levels of education, capacity and determination. I believe that the aspiration for progress is incredibly inspiring.

Thank you.

Journalist: Nominbileg. P